What makes an effective science communicator?

For Dr. Heather Leslie, a professor at the University of Maine’s School of Marine Sciences and former director of the Darling Marine Center, communicating about the challenges facing ocean ecosystems today—as well as potential solutions—is a critical part of her work. Her team of marine conservation scientists engage with a wide range of collaborators to support marine stewardship and management that benefits both nature and people.

“When I am communicating with others about my science, I try to put myself in their shoes. What does this person find interesting? What motivates them?” said Dr. Leslie. “When I take the time to ask myself these questions, I usually give clearer and briefer explanations of my science. And I am then able to ask better questions of others, encouraging them to think scientifically, too.”

What Is Science Communication?

Science communication involves distilling the technical aspects of scientific research into language that the public can better relate to and understand. It’s an important skill for any scientist to have, as the public often needs to grasp the basics of this research to make informed decisions that will impact their lives as well as future generations. Science communication also helps others get excited about learning and connecting with the world around them.

“The wonder that I experience as an ecologist studying how marine ecosystems work is something I share with others whenever I can—whether they are schoolkids tidepooling with me, or neighbors who have taken time out of their busy schedules to join me for an afternoon presentation,” said Dr. Leslie.

Scientists who receive public funding also have a responsibility to share what they learn.

Dr. Leslie notes that she has seen a larger emphasis put on engaged or solution-oriented research over the last decade.

“There definitely is a greater expectation among many of us that scientists not only have a responsibility to communicate their work, but also to translate it into action when they can,” she said.

Common Science Communication Challenges

However, because most people are simply not trained as scientists, challenges can arise when trying to communicate more complex research. If people don’t understand the terminology being used, it can be all too easy to tune out scientists trying to explain complicated topics.

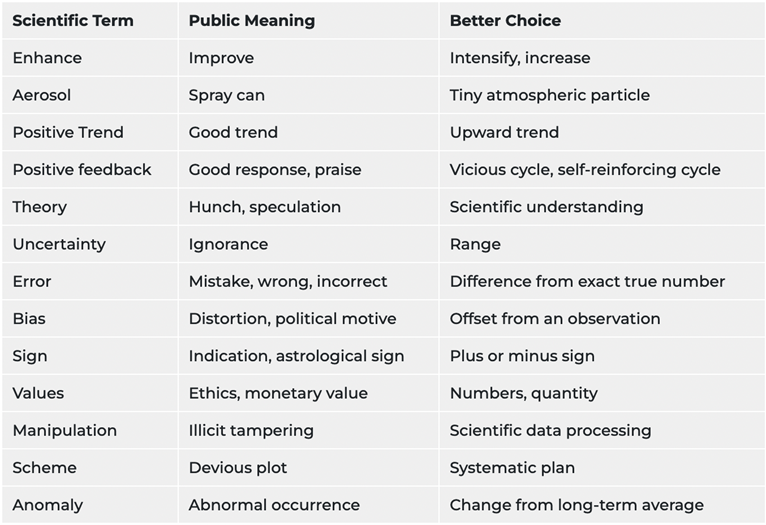

A 2011 article in Physics Today shows how many words that seem perfectly normal to scientists are often confusing to the average person. The authors provided a helpful table of terms having one meaning among scientists and a different, sometimes contradictory, meaning among the public.

For example, communicating about climate change illustrates the power of words. The term “consensus” suggests to some that climate change is just a matter of opinion, rather than an evidence-based theory. The verb “contributes” might be misunderstood by the public to imply that the contribution of human activities to a warming of the climate could be small, instead of the primary cause.

A communication breakdown between scientists and the public can lead to mistrust and misunderstanding of accepted research. Today’s scientists face an important challenge: communicating about climate change in ways that inform without inflaming, educate without being academic, and are concise yet accurate.

How to Talk to the Public About Science

Remember, effective communication is as much about listening as it is about what you say.

“We scientists are often trained to speak well, but not necessarily to listen well. Yet both listening and speaking are crucial for effective interpersonal interactions,” said Dr. Leslie. “I do my best to focus on listening when I am building relationships with new people.”

For scientists looking for some specific recommendations, the American Society for Cell Biology provides toolkits that outline best practices for science communication. Tips include:

- Know your audience

- Connect your work to the big picture

- Avoid jargon

- Use metaphors that connect everyday experiences with your topic

- Be enthusiastic—your excitement can excite others

Dr. Leslie points out that building trust takes time, and there are few shortcuts.

“Show up. Listen. Be ready to explain why you are present—whether it is a public meeting or on the local fish pier—but mostly listen and learn,” she said.

Sharing Your Science with the Media

Scientists also work with reporters to get their research out into the world. Dr. Leslie acknowledges that while social media has become an important way to connect with community members, there is no replacing the local newspaper. She often writes press releases to share information.

One challenge for many scientists is that typical science communication (such as published journal articles) starts with a lengthy discussion of the background to frame the question and the methods used to examine it, with the results reported at the very end. Most news stories, on the other hand, flip that approach to start with the bottom-line takeaway as the lede.

The University of Arizona shares practical suggestions to help scientists interact with the media. When speaking to a journalist about a study, start by telling them the question you were seeking to answer, what you learned, and what the results could mean for others. It’s important to be very clear about any limitations to guard against misrepresentation of the findings or sensationalism. Use the power of repetition to reiterate the main point you want to make in clear, simple language.

The Role of Communication in Community Science

Dr. Leslie’s lab is active in what she calls “engaged research” that is developed in partnership with local shellfish harvesters, fishermen, high school students, and other community members. This type of community engagement relies on communication and trust.

She co-founded the Damariscotta River Estuary Community Science Project in 2019, a initiative focused on the commercially valuable bivalve shellfish species of the upper estuary. Since that time, feedback gleaned from participating community members has been invaluable as they work together toward more sustainable coastal ecosystems.

The project tracks changes in shellfish populations and the broader ecosystem and reports their findings to a municipal Shellfish Conservation Committee based in a nearby coastal community. They are also able to document local knowledge about how these changes have occurred over the last two decades, before information was systematically gathered at a local scale.

“While I still pursue research questions because of scientific curiosity, most of the work I’m focused on is in response to questions posed by my neighbors and other community members,” said Dr. Leslie.

How You Can Become a Science Communicator

While we may not all be trained scientists, many of us incorporate scientific thinking into our daily lives by embracing our curiosity, experimenting, and following the data. Anyone looking to improve their science communication skills can access the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) Communication Toolkit for help in applying the fundamentals of communication to scientific topics.

While science communication is not without its challenges, for Dr. Leslie, it is an especially important and rewarding part of her work.

“I have found that I am a better scientist for sharing what I do,” she said. “When I share my scientific thinking with broader audiences, I often am encouraged to think about the questions I am asking in new ways and gain information I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.”