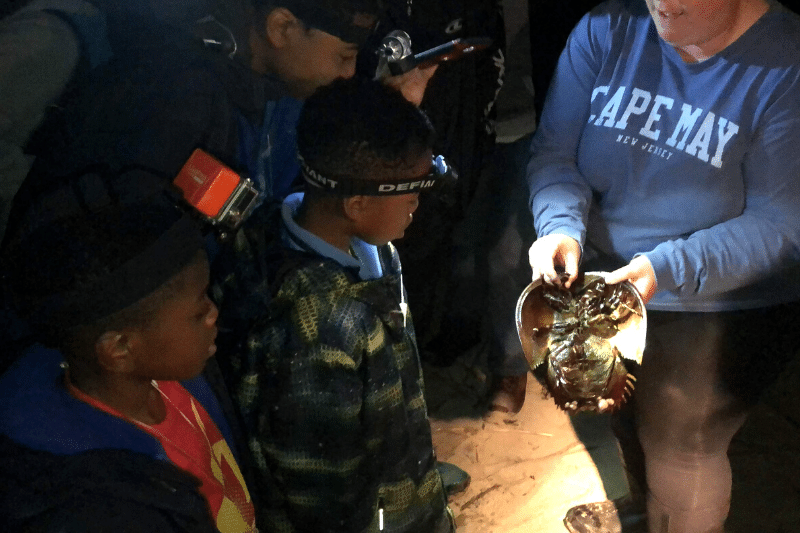

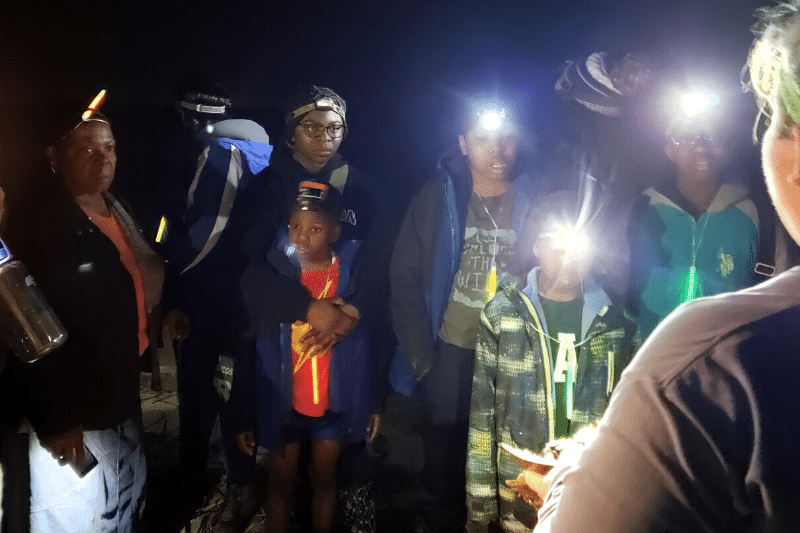

Nothing says summer like a family trip to the beach. The air of anticipation as everyone piles into the car with their bathing suits and beach towels and you hit the road, daydreaming about the day's activities—the sweet smell of sunscreen, the rhythmic sound of the waves, the slimy feel of a horseshoe crab's shell as you prepare it for tagging!

“My sister-in-law swore she wasn't going to touch one,” said Chanda Bennett. “She gave a little squeal when she picked it up, but she quickly became an expert.”

Just another day at the beach for Dr. Chanda Bennett. An advising dean at Columbia University in New York City, Bennett has taken her husband and three sons on similar horseshoe crab tagging trips to Cape May in the past, but this was the first time with her extended family.

“They thought we were completely out of our minds,” Bennett said with a wry smile.

Despite some initial apprehension, Bennett's patience and enthusiasm eventually won them over, and a new family ritual was born. It's all in a day's work for this animal lover and scientist working to promote the necessary role of environmental research in everyday life.

“This experience helped my family get to know me a little better, as someone who does this type of work, and it was eye-opening for them to see that this research is done in a local area,” said Bennett. “It's not elsewhere, it's here. And now they want to come back and do it all again.”

Greatness From Small Beginnings

Bennett's fascination with and reverence for the natural world has been a part of her life as long as she can remember. Growing up in the dense urban landscape of Brooklyn, she spent much of her formative years seeking out whatever green spaces she could find, with nearby Prospect Park acting as her “second backyard.”

This pastoral childhood was upended when she began experiencing hearing loss at a young age. Her doctors noted that this condition could become permanent, advising her parents to prepare for her to completely lose her hearing. Suddenly, Bennett's sojourns into the outdoors began to shift focus.

“My parents wanted me to be able to enjoy the parts of nature that I might lose if I became legally deaf,” said Bennett.

Her father would take her on regular outings to Central Park, but before she could go play with the other kids, she had important work to do first.

“It was like torture at the time,” laughed Bennett. “I had to sit and close my eyes, and I had to listen to my surroundings. And then I had to tell him what I heard and describe it, as well as sign it [using sign language].” She slowly worked her way through the different signs—bird, squirrel, car—as children laughed and played in the background. “We did this often enough that it kind of became my world—being able to just sit and listen and enjoy that silent time.”

Walking the “Crooked Path”

Fortunately, after undergoing surgery, Bennett was able to restore her hearing, but the trips to Central Park with her father continued to resonate with her. She decided she wanted to pursue a career in environmental studies, though she wasn't sure where to start.

“I loved animals from an early age, but I did not want to be a veterinarian,” said Bennett. “But at that time, in the eighties and nineties, there weren't many other options in that field that I knew of, or my parents knew of.”

Bennett describes her path to her career as a scientist as “a bit crooked” due to the lack of professional mentors in her community. “I think it kind of hindered that growth I was expecting of myself,” she said.

But she was determined to follow her passion for environmental education, and eventually settled on studying one of the most misunderstood city-dwelling creatures—the bat.

“Everybody's used to birds or raccoons or possums in an urban environment,” said Bennett. “But you rarely hear about bats.”

“There Are No Bats in Brooklyn”

Bennett's fascination with bats began in the late nineties while studying wildlife management in Kenya. Each night, she would be surrounded by a cloud of flying bats as they fed on mosquitoes and other nocturnal insects, an experience she wasn't accustomed to growing up in New York.

“I didn't think there were bats in the city,” said Bennett. “At the time, I thought, there are bats in Africa, bats in Asia. But there are no bats in Brooklyn.'"

In what Bennett describes as an “aha!” moment, as she sat around the campfire on the African plains, her curiosity concerning these creatures triumphed over her fear and she knew she wanted to devote her time to learning as much as she could about bats. However, instead of becoming a crime-fighting vigilante like a certain other bat-fan, she decided to study the presence of bats in an urban setting.

“When I discovered there were in fact bats in Brooklyn, I thought it was the most amazing thing ever,” said Bennett. “They're such misunderstood creatures. They've had to come up with some impressive behaviors to survive in a dense urban setting. Learning how humans impact them is equally as important.”

Citizen Science: A Family Affair

Now with children of her own, Bennett has tried to instill in them a similar level of engagement with the environment as her parents did with her.

“I think the difference is, where I had more opportunities to engage with the environment passively by visiting parks and the zoo, my sons are now learning more about the environment actively by doing,” she said. “We didn't have many opportunities for citizen science when I was growing up.”

While working as the manager of education for the New York Aquarium, Bennett was able to access a number of citizen science projects in the area and decided it would be fun to involve the whole family.

“I tried to include the kids at an early age,” said Bennett. “My oldest son was only six months old when I took him on his first bat survey.”

Bennett's three sons, now in their pre-teen and teenage years, have grown up treating citizen science projects like beach cleanups and BioBlitzes as if they were common extracurricular activities like football or piano lessons. And while it makes for a packed schedule, Bennett is happy to help grow their natural curiosity toward the environment.

“It's a way for me to help my kids recognize that you have a role in your environment, and you have a responsibility to that environment,” said Bennett. “It's not every year we do something, but we try to do some amount of community or citizen science work as often as we can. And I think it became something of a family tradition, like "This is normal; this is something we always do.'”

Greening STEM in Your Own Backyard

Bennett's oldest son, Darius, was able to showcase his citizen science expertise by participating in a Greening STEM project with his fellow classmates at Benjamin Franklin Middle School in Teaneck, New Jersey. Thanks to a partnership with the Teaneck Creek Conservancy, Samsung, and BFMS, NEEF helped provide a hands-on field experience for 7th and 8th-grade students at their local watershed, engaging them in a water quality monitoring project and a macroinvertebrate biomonitoring study in and around Teaneck Creek.

“Darius had already been there because we've hiked through that area before, so it was familiar to him,” said Bennett. “Of course, he wanted to show everyone all these secret spots he had found, but unfortunately they didn't have time.”

Bennett sees the potential of programs like Greening STEM to foster an interest in citizen science projects like the ones her family has participated in for years.

“What I like about the Greening STEM project at Teaneck is that it used a local resource that I think is underused and that I think some people don't care about or even know exists,” she said. “Being able to take kids to this environment where many of them may not have been before, even though they live in that community, is huge because it has now seeded their thoughts. And how that seed grows in their minds will be determined by a number of other factors.”

“It's a way for me to help my kids recognize that you have a role in your environment, and you have a responsibility to that environment,” Chanda Bennett, Mother, Scientist, and Advising Dean at Columbia University

How to Get Your Family Involved in Citizen Science

Perhaps you've wanted to get your family into citizen science for a long time, or maybe you've never thought about it once until now. No matter your situation, Dr. Bennett has some helpful advice for incorporating citizen science projects into your family's day-to-day lives:

Tap into Your Kids' Interests

When thinking about citizen science activities for the whole family, it's important to consider what your kids already enjoy doing. Do they love the water? Try a beach clean-up or water quality monitoring project. Are they big into computer gaming? Look into virtual volunteering projects like NASA's GLOBE program. The important thing is to get your kids excited about what they're doing and let them take care of the rest.

“My kids love to talk about the projects we've done when they get back to school,” said Bennett. “As an educator, that's so fantastic, because they are informally educating their peers and teachers about what they experienced, and that gives them some self-power over the knowledge they've gained.”

Consider Your Community

While Bennett acknowledges that it may be easier to find citizen science projects in her area than other parts of the country, there are still plenty of places the average American can look for ideas.

“Nature centers are great, as are children's museums,” said Bennett. “Local parks will occasionally host activities as well.” And don't forget your own backyard!

Make Your Own Citizen Science Project

If you're really struggling to find citizen science projects in your area, why not try making your own? There are countless resources out there for DIY projects, including the EE at Home section of NEEF's website. Don't let a (perceived) lack of options stop you from taking action.

“When I was growing up in Brooklyn, there was a small street triangle that had trees and grass and some seats where you could relax,” said Bennett. “One day, this little square plot of plants appeared, and it turned into a butterfly garden. Next thing you know, the whole community wanted to care for and expand this small garden. If you can think about it, you can make it!”

It's OK if You Don't Have Time

Bennett understands she is lucky to have the flexibility in her family's schedule to make time for citizen science projects.

“I feel for those families where living is tight and time is a luxury,” said Bennett. “I want to acknowledge them and tell them it's OK. Even if you can't take action now, knowing that the possibilities are there is just as important.”

She suggests incorporating citizen science into your existing family time. For example, if you like watching nature programs together, get a map and place a pin whenever a location is mentioned. If you don't have a yard or green space nearby, try growing pollinator-friendly flowers on your fire escape or windowsill and documenting the creatures that stop by.

Increasing Inclusivity in Citizen Science

Perhaps the biggest benefit of participating in citizen science projects as a family is it provides a safe space for those who identify as Black, Indigenous, people of color, and folks from other marginalized communities.

“Participating in citizen science projects as a family makes for a more comfortable environment, and provides a space to be curious without judgment,” said Bennett.

During one of Bennett's now-infamous family beach trips to tag horseshoe crabs, the coordinator of the project pulled her aside. She said that Bennett's group of 14 family members and friends was by far the largest number of African Americans she had hosted at one time, and she wanted to know how they could continue that level of engagement.

“She said to me, 'How can we get more people of color to participate?' She thought it was amazing,” explained Bennett. “It's not a stereotype I'd like to harp on, but there may be reasons why [people in those communities] don't feel comfortable going out alone. There's comfort and safety in numbers.”

Inspiring the Next Generation of Citizen Scientists

At the end of the day, Bennett is just happy to be able to share her love of nature with those she cares about, and to pass on that knowledge and enthusiasm to the next generation of environmental stewards.

“I think having them take a moment to stop and recognize that your world is bigger than you think is purposeful,” said Bennett. “It helps to build compassion and responsibility and accountability, no matter what the circumstances are.

“It all has a place in how we learn and how we relate to the environment.”