An expert offers tips for gaining public buy-in on complex health matters

1942. The South Pacific. US troops fighting in the Pacific Theater were facing down their toughest foe yet—the humble mosquito.

According to the US Army Center of Military History, Army medical personnel treated over 47,000 cases of malaria that year, with roughly a quarter of all troops in the area being infected.

Things back at home were not much better, either. While not reaching the levels seen overseas, malaria was a common problem throughout the southern part of the US, particularly in areas where military training bases were located. With this in mind, the US government established the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas to study methods for controlling the spread of malaria and other vector-borne diseases to help turn the tide in this battle—and the war.

1946. Atlanta, Georgia. With World War II now over, scientists began to shift their focus to combating malaria on US soil. Building on the success of the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas, Congress established the National Malaria Eradication Program, a partnership between state and local health agencies in 13 southeastern states. They also created a new organization to oversee its completion: the Communicable Disease Center (CDC), later renamed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By 1949, the United States was declared malaria-free.

A country in crisis

America has had its share of public health crises throughout history. In each instance, a strategic, unified response focused on keeping the public educated and informed was necessary to turn the tide and prevent unnecessary illness and death.

However, as the country faces down one of the deadliest pandemics in over a century, public health officials are struggling to convey clear and effective messaging on COVID-19 in the face of public apathy and rampant misinformation. This raises questions for how organizations should approach messaging strategies for public health matters both now and in the future.

How do you reach people, especially those who are most at-risk, when they are either unable or unwilling to receive the message? We turned to an expert for advice: Dr. Cedrek McFadden of Greenville, South Carolina.

“With understanding comes better action”

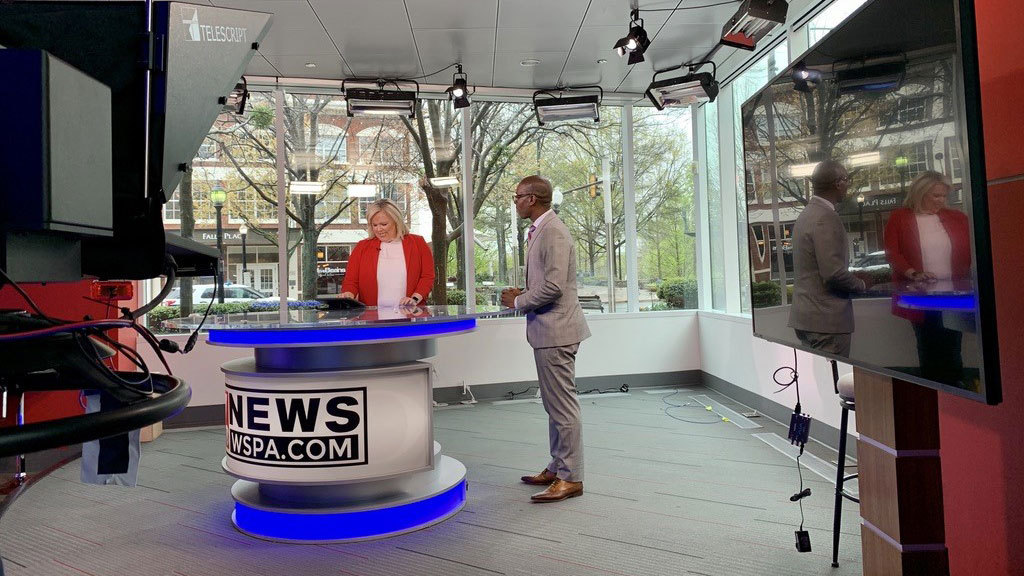

Dr. Cedrek McFadden is a board-certified surgeon, speaker, writer, and mentor who regularly appears as a health expert on television, radio, and in print. In addition to his work as a colorectal cancer specialist and clinical assistant professor of surgery, he is a tireless advocate for public health issues in communities across America.

“When I was growing up, several members of my family had illnesses—my grandmothers, my grandfathers,” said Dr. McFadden. “I saw the value that doctors had in their lives to help them regain their health.”

However, he also saw the difficulty his family members had with understanding what the doctors were telling them, even when they were engaged and listening intently.

“One of the big challenges I sought to overcome was to help people understand the health issues that affect them,” he said. “I think with understanding comes better action, and if people can make better-informed decisions about their health, they may be able to come off certain medications or avoid surgery, and hopefully live a more fulfilled life.”

After graduating with honors from Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, Dr. McFadden earned his medical degree from Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia. His experiences as a grandson, nephew, and med student inspired him to start lecturing at hospitals, civic organizations, churches, and community groups.

“I don’t think the role of a doctor is just in the examination room,” he said. “A big part of it is messaging—how to prevent illnesses, or making it easier for patients not to have to be on medication. But it has to be proactive.”

From colon cancer to COVID, a disparity in disease

Though Dr. McFadden is not an infectious disease specialist, he has continued to lecture on the dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic by drawing a line from this disease to one with which he has significant experience: colon cancer.

“I think there are definitely parallels,” he said. “I’ve spent a lot of time talking about colon health and cancer in general. With regular screening, colon cancer is a mostly preventable illness.”

Though countless studies have shown that simple steps such as social distancing, proper hand hygiene, and wearing a mask can significantly reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19, the public is still misinformed about how the virus is transmitted and who is at risk. Dr. McFadden has witnessed a similar lack of information surrounding colon cancer treatment and prevention.

“They’ve heard horror stories, a lot of which are not true,” said Dr. McFadden. They have misconceptions about who gets colon cancer, how they get it, and how to prevent it.”

“There’s also a disparity in how colon cancer is treated and how it presents across racial lines,” which echoes an issue many communities are seeing regarding COVID-19, he said.

In addition to people with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, and asthma, long-standing systemic health and social inequities have put many people from racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19. According to the CDC, these additional risk factors include access to healthcare and housing, educational and income gaps, and occupational status.

“African Americans are three times more likely to get COVID-19,” said Dr. McFadden. “They also have higher rates of hospitalization and account for almost 20% of COVID deaths.”

The key takeaway, he said, is no matter what public health issue you are dealing with, “the need for good messaging is just as important and can save lives.”

Changing hearts and minds by conquering fears

With COVID-19 vaccine distribution underway across the country and millions of people already inoculated, there is light at the end of the tunnel. However, there is also public uncertainty about the safety and efficacy of the new vaccines.

Dr. McFadden has heard all sorts of concerns.

“People have told me it was rushed, or they haven’t worked the kinks out yet, or ‘I don’t want to be a guinea pig,’” he said.

However, he stressed the importance of not dismissing these anxieties as silly or trivial. When the ultimate goal is total public buy-in, he said, you can’t afford to leave anyone behind.

“You need to speak to the fears and to the hesitancy people may feel, because often that is what’s truly holding them back,” Dr. McFadden said.

He suggested a better approach—addressing public concerns with facts and evidence.

In the case of COVID-19, this means visiting the CDC’s vast online resources covering the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and how they differ from traditional vaccines that use weakened or inactive strains to trigger an immune response. It’s also worth mentioning that the current COVID-19 vaccines are far from “rushed”—they are built upon years of research that began shortly after the outbreaks of SARS in 2002-2003 and MERS in 2012.

That’s not to say the development of a COVID-19 vaccine isn’t revolutionary. In fact, it may go down as one of the crowning achievements of modern science, and it couldn’t have happened without the collaboration of multiple groups, from the US government and National Institute of Health (NIH) to nonprofit organizations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Musician Dolly Parton even famously contributed $1M to Vanderbilt University’s COVID-19 vaccine research, which helped directly fund one of the vaccines.

“When it comes to something like the COVID vaccine, you can’t bully people into accepting it,” said Dr. McFadden. “You can’t push them or shame them. You can’t just report about it on the news. It’s going to take one-on-one conversation with people to address their issues in order to make an impact.”

Strategies for successful public health education

With such a fractured media landscape, how do you educate communities and share factual, evidence-based information while dispelling myths to ensure people make informed decisions about their health?

“It’s important to keep in mind that the change in thought or acceptance you’re looking for may not be on your timetable,” said Dr. McFadden. “There’s a tendency to want automatic conversion, but that may not happen, or it may happen in stages. A patient may hear a piece of what I say, they may have a conversation with a friend, or read something different, and collectively that will bring them to a certain point.”

Counterintuitively, he recommends against sounding the alarm on public health issues too often, otherwise you risk alienating your audience. He likens it to hitting snooze on an alarm clock: “If you keep shutting the alarm off because it keeps ringing, at some point you just don’t hear it,” he said.

While all of this may sound like a difficult tightrope to walk, it doesn’t have to be. Consider using the following strategies to help make the most of your public health-related messaging.

Get to know your audience

Early in his career, Dr. McFadden said he would take any opportunity to speak with the public, no matter where, when, or how big—or small—the audience.

“I once attended a health fair at a local church. It was maybe four or five older ladies in the church basement, and we just talked about diabetes!” he said.

You don’t have to visit every church basement in the country to get your message out there, but should take advantage of other platforms such as social media and local news to put your message where people already are instead of spending time and energy to get them to come to you.

Make your message easy to understand

If your audience can’t grasp what you’re trying to teach them, they’ll have a hard time taking it to heart, much less passing it along to their friends and family. Word choice is important; make sure you’re explaining things in a way that someone who isn’t a medical professional can understand.

An easy method for gauging your audience’s understanding is to have them tell you what they know and where they need more information.

“I like to ask my patients, ‘Explain to me what I said to you today,’” said Dr. McFadden. “Often, the way that they explain it is the way that I need to be explaining it to them, and so I will try to incorporate some of what they’ve said in the future.”

Vary your messaging strategy to fit your audience

Even if you’re doing your best to explain things simply, people still may have difficulty following you. Keep in mind that we all learn at our own pace, and what works for some individuals may not work for others.

“It’s important to not rely too much on just verbal explanation—you can also use visual aids to help increase a person’s understanding,” said Dr. McFadden. Consider switching up your messaging strategy with illustrations or video to make certain concepts easier to grasp.

Establish trust

It seems obvious, but if your audience doesn’t trust the messenger, they are not likely to trust the message, either. You must work to establish and cultivate trust before you can begin to change people’s hearts and minds.

“It’s not just about the message itself, but also how it is presented,” said Dr. McFadden. “What you’re trying to convey could be extremely important, but if it’s presented poorly, it may not stick.”

Likewise, if you have a great delivery but the message has no substance—or is just perceived that way—you are in danger of losing the trust you’ve earned.

“You can’t build trust just by saying you’re trustworthy; you have to demonstrate you know what to do with that given trust,” said Dr. McFadden.

It’s all about “real talk”

Ultimately, the success of any public health initiative comes down to trust. People have to believe that their best interests are being represented, but more importantly, they have to believe in the ability of public institutions to help improve their lives. Unfortunately, for some communities, that trust has been betrayed through a history of discrimination and neglect.

While good work is being done to restore the public trust, the best tool we have now is the simplest one—authenticity. If an organization is committed to making a difference, the work they’ve done should speak for itself.

“People need to see the passion behind your message. See that it means something to you,” said Dr. McFadden. “It all comes down to having ‘real talk’ with people.”