Picture this: It's a beautiful summer Saturday. You've been looking forward to checking out the new hiking trails at your local nature preserve all week, and you're finally ready to get out there and explore.

Of course, you made sure to do your research first. The park's website lists a number of accessible features, including parking and restrooms, but as you roll out of bed and climb into your wheelchair, you're not thinking about all that. You're too busy daydreaming about the emerald leaves, the rich smell of bark and loam, and the calm quiet interrupted only by the occasional bird call.

It's an hour's drive to the park, but the minutes fly by like the passing cars on the interstate—until suddenly you're there at the trailhead.

Lost in excitement, at first you don't notice the terrain is rockier than expected. And is it just you, or is the grade a bit steeper than normal for an accessible trail? It's not until you come upon a deep gully, the only path across being an elevated wooden bridge with no wheelchair ramp, that it finally registers: this trail isn't safe for you. Your dream of losing yourself in the splendor of nature will have to wait for another day.

Defeated, you turn around and slowly make your way back to the parking lot.

- - -

Despite nationwide efforts from federal and state agencies to expand access to America's public lands, this story remains a familiar one for many in the disability community.

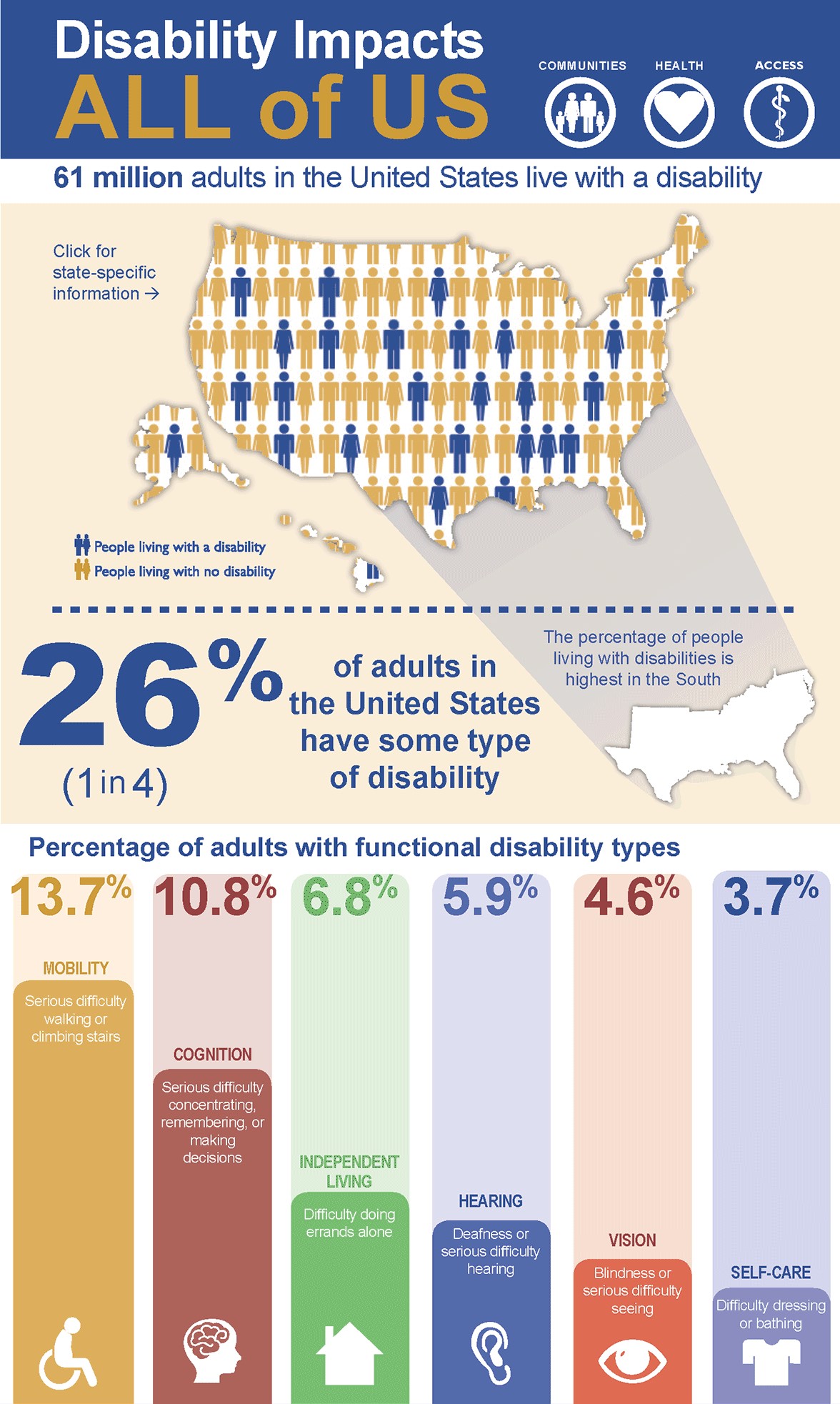

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 61 million Americans are living with a disability and 26% of adults in the US have some type of disability. The National Park Service estimates that a minimum of 28 million visitors with disabilities visit national parks annually—and that's not counting the family and friends who accompany them. Ensuring that everyone truly has access to our shared public lands and waters is an ongoing challenge supported by activists, outdoors organizations, and land management agencies.

A Lifetime of Advocacy for Accessibility

This challenge is nothing new to Bonnie Lewkowicz. Bonnie has spent the past four decades working to increase access to sports and outdoor recreation for people with disabilities, first as an intern at the Bay Area Outreach and Recreation Program (BORP) in Berkeley, California, and now as the program manager of Access Northern California (ANC), accessible tourism and outdoor recreation nonprofit she founded and merged with BORP in 2016.

“Who would've ever thought that I'm getting my second career at 65,” joked Lewkowicz.

Disability rights advocacy is a lifelong passion for Lewkowicz. After a tragic dune buggy accident led to quadriplegia that required the use of a wheelchair, she decided to pursue a career in recreational therapy.

“Having been a very physically active person, I was frustrated by the lack of those kinds of opportunities [for the disabled community],” said Lewkowicz. “I saw the benefits of participating in sports and outdoor activities and wanted to help other people get that in their lives.”

While Lewkowicz said that conditions have certainly improved over time, there's still a lot of work to be done to achieve the ADA's goal of equal opportunities for people with disabilities, especially in parks. She founded ANC to address the gaps she encountered while sourcing reliable accessibility information for people with mobility disabilities.

“We're not always able to get that information from park websites,” said Lewkowicz. “Which is kind of a big deal, because if people don't know whether a park is accessible or not, they might choose not to visit.”

If people don't know whether a park is accessible or not, they might choose not to visit,

Bonnie Lewkowicz, Program Manager, Access Northern California

Increasing Access to Nature for Public Lands Visitors

With this in mind, NEEF partnered with Toyota Motor North America to establish the 2022 Driving Mobility and Accessibility on Public Lands Grant. Using funding from vehicle sales of the Toyota Sienna Woodland Edition, NEEF awarded $150,000 in grant sponsorships to eight organizations across America working to address mobility and accessibility considerations on public lands and waterways.

As one of the awardees, Lewkowicz and her team have partnered with East Bay Regional Park District to develop the “Access to Nature” project.

Building on the success of BORP's website of accessible trails, Access to Nature is in the process of surveying and adding 15 access-detailed trail reviews and five camping opportunities in East Bay Parks, helping visitors easily identify the trails that best fit their needs. BORP has also begun leading several trips in ADA-accessible buses to these parks.

“The main goal is to conduct accessibility surveys to populate the website with more information about where people can go to find an accessible trail or an accessible park, and then also to do some trips out to those parks,” said Lewkowicz.

In December of 2021, Lewkowicz and BORP, as well as eight student volunteers from nearby San Francisco State University, accompanied 17 individuals with mobility and vision disabilities on an outing to Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve in nearby Contra Costa County. The mine had been closed for over a year to make access improvements, and the group was invited to tour the facilities before it officially opened back up to the public.

Upon arrival at the mine, park staff had set up interpretive sensory tables where visitors could touch, smell, and listen to some elements found in the park, such as animal pelts, basalt, a variety of local plants, and recordings of bird calls from native species. They also provided a picnic lunch for all attendees.

It was fabulous,” said Lewkowicz. “The park asked for our feedback on the access improvements, and people really loved it."

Since then, BORP has conducted several more outings to public lands in the East Bay Regional Parks system. To date, they have provided approximately 40 members of the local disability community with the opportunity to enjoy accessible outdoor experiences.

Though she says advocacy is a “byproduct” of Access to Nature, Lewkowicz is pleased with the positive response to her surveys from park staff.

"So far, the response has been great,” said Lewkowicz. “When I audit a park or trail, I'm not looking to see if it's in compliance with regulations. I'm just reporting on what's there. But I will contact the parks to let them know 'I came across this barrier' or 'This could be improved.' By doing these surveys, it has inadvertently helped increase access as well.”

How Can Public Lands Become More Accessible?

Lewkowicz has written several books on accessibility in outdoor recreation—including “A Wheelchair Rider's Guide: San Francisco Bay and the Nearby Coast”—and she has some advice for local, regional, and even national parks looking to provide a welcoming space for visitors of all abilities.

“Just saying something is accessible isn't the full story,” said Lewkowicz. “People need as much information as possible so they can make an informed decision about what park or trail is going to work for them.”

Update Your Website to List Accessible Features

Throughout her many years of conducting accessibility surveys, Lewkowicz found that, while park websites have done a decent job of listing certain areas as “accessible,” they don't always provide much in the way of specifics.

“It's like, 'Well, is the bathroom accessible? Is there parking?'” she said. “In my career, I have made it a point not to identify something as just 'accessible,' but to say, 'Here are the accessible features. You decide if it's accessible for you.'”

When evaluating a park's website for accessibility information, Lewkowicz looks for the following items:

- Bathrooms

- Parking

- Picnic areas

- Pathways between facilities

- Access to trailheads

- Specific trail information: surface, width, terrain, and slope

Lewkowicz and ANC are currently working with mobile hiking app AllTrails, which has offices based in the San Francisco Bay Area, to make this accessibility information more readily available to its users.

Follow the Tenets of Universal Design

American architect, designer, and educator Ron Mace gained international acclaim for developing the concept of universal design, which he described as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” Universally designed sites and facilities that are accessible and inclusive provide equal opportunity not only for people with disabilities but for all people who wish to enjoy the space.

Unfortunately, Lewkowicz sees this important design concept neglected far more often than she would like.

“My niece contacted me recently because she's going to school for landscape architecture and has to build an ADA-accessible trail as a project,” said Lewkowicz. “I asked her if she studied universal design in school and she said, 'What's that?' So it's a constant educational process.”

Bring Together a Diverse Group of Voices

One of the easiest ways to ensure your park is accessible to the disability community, Lewkowicz says, is to have people on your staff who understand those experiences. For example, while she does not have a vision disability herself, she works closely with several colleagues at BORP who are partially or fully blind. When conducting an accessibility survey, she makes sure to take their lived experiences into account as well as her own.

“It used to be good enough to just declare something as 'accessible,' but nowadays, it doesn't paint the whole picture,” said Lewkowicz. “There's access for different types of disabilities. The wheelchair symbol [International Symbol of Accessibility] doesn't mean anything to a blind or low vision person if there's no braille on the doorway or a lack of braille signage in general.”

Don't Stop at Accessibility

Following that point, Lewkowicz cautions parks not to get too swept up in trying to follow the letter of the law at the expense of their visitors' enjoyment of the space.

“There are things you can do to make people feel welcome that aren't just about making a trail accessible,” she said.

For example, East Bay Regional Parks is working to train their docents to offer more interpretive activities like the previous outing they hosted at Black Diamond Mines. Providing items from the park for visitors to smell, touch, listen—even taste—can help them experience the natural beauty of these spaces in a more impactful way than traversing a simple paved path around the parking lot.

Embracing the Power of Parks for Everyone

In the end, Lewkowicz is excited to see that organizations like NEEF are putting a focus on mobility and accessibility improvements when handing out grants for public lands.

“I've been doing this work for 25-plus years, and rarely did I see foundations cover anything related to getting [the disability community] outdoors,” said Lewkowicz. “When I first learned of the grant, I was super excited because it was the first time that any funder had ever recognized that information barrier. I went to [NEEF's] website and I was like 'Oh wow, this organization's really getting it.'”

Lewkowicz hopes that her work with ANC and BORP will help make it easier for everyone, regardless of their abilities, to find the information they need to get outdoors and enjoy the physical and mental benefits of spending time on their local public lands.

“Our parks are for everyone,” she said. “There's no vacation from disability, but getting out in nature can give you a reprieve and make it not the focus of your day—there's value in that.”

Interested in learning more about how to apply for a NEEF grant? Visit our grants page, where you can read our seven tips for writing an effective grant proposal and view the NEEF Glossary of Terms/FAQ for a list of the most common questions about NEEF grants.