Saguaro National Park is known for its towering cacti that dot the landscape and its awe-inspiring sunsets.

Located in southern Arizona, the park is less than 30 minutes from the nearest major metropolitan area of Tucson. In 2019, the park saw its busiest year to date, surpassing 1 million visitors for the first time ever. However, many residents in the communities immediately surrounding the park have never visited it.

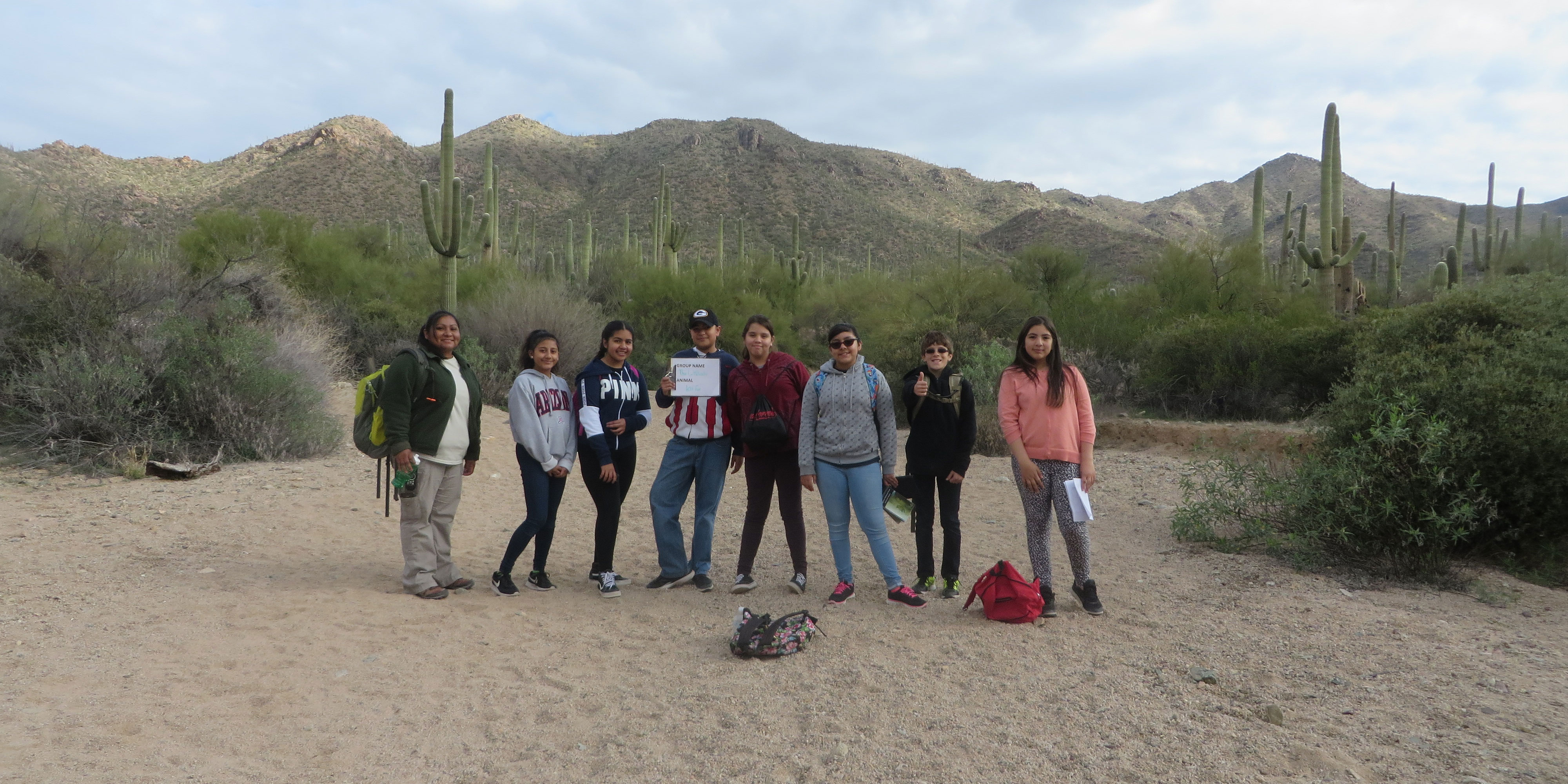

Thanks to an innovative new environmental education program, this may soon change. Supported by the Friends of Saguaro National Park, a dedicated team of educators is engaging youth from local communities by providing opportunities for genuine exploration, critical thinking, and quality time in Saguaro National Park.

The Lost Carnivores Wildlife Monitoring and Citizen Science Project is designed to engage professional and amateur scientists in hands-on investigation and on-the-ground data collection in Saguaro National Park and other natural areas in the Tucson Mountains. Originally launched in 2005, the Lost Carnivores Project was established to monitor the health and well-being of five small carnivore species in the Tucson Mountains area: the Common Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus mesoleucus), the Western Spotted Skunk (Spilogale gracilis), the Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis), the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis), and the Common Raccoon (Procyon lotor).

At the time, biologists from the park started noticing startling declines in the populations of these five species. In response, scientists began using infrared-triggered wildlife cameras—which are used to take photos of animals when people are not present—to track and study these small carnivores over several years.

Over the years, the Lost Carnivores Project has grown to include a robust environmental education program that brings youth participants to the park. NEEF has had the pleasure of supporting the Lost Carnivores environmental education program through our Greening STEM grant program.

When students start to pick up rocks, look at the colors of things, and question what lives in all these holes, it tells me that they have not had exposure [to the outdoors], but they are interested.

Sita Stanfield, Environmental Education Next Generation Ranger, Saguaro National Park.

During the educational programming, middle and high school students go into the field to check wildlife cameras that have been set out by previous students. The students then have the opportunity to set their own cameras that are checked by a future group of students a few weeks later.

This on-the-ground data collection provides students with the opportunity to practice real-world wildlife monitoring techniques while working alongside seasoned park professionals. Students also gain the opportunity to use STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) in practical, real-world applications.

Youth participants are expected to form hypotheses about the best location within the park to place each wildlife camera, and what height and angle to position the cameras in order to photograph each target species. They are also responsible for tracking the location of wildlife cameras using handheld GPS units in the field and online geographic information system (GIS) tools in the classroom. All of the data and photos collected by students is shared with park biologists and used to inform land management decisions within Saguaro National Park.

When asked how they felt about their time in the field, one of the students responded, “I felt like a real scientist.”

You can check out some of the photos that student “citizen scientists” have taken on their wildlife cameras by visiting Saguaro National Park's Flickr page. For more information about citizen science, including how you can get involved in a project in your area, visit NEEF's Citizen Science resource page.